A recent CNN article titled “Black or ‘Other’? Doctors may be relying on race to make decisions about your health,” discusses how race has both historically affected and currently impacts the medical decisions that doctor’s make and the subsequent care that patients receive. Among the examples it covers is the controversial eGFR (Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate), which is used to measure kidney function. eGFR is calculated through a formula that includes your blood creatinine level (creatinine is a waste product that is filtered from your blood by your kidneys) as well as other variables such as age, sex, and race. However, as CNN states, “When it comes to race, doctors have only two options: Black or ‘Other’.”

A recent CNN article titled “Black or ‘Other’? Doctors may be relying on race to make decisions about your health,” discusses how race has both historically affected and currently impacts the medical decisions that doctor’s make and the subsequent care that patients receive. Among the examples it covers is the controversial eGFR (Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate), which is used to measure kidney function. eGFR is calculated through a formula that includes your blood creatinine level (creatinine is a waste product that is filtered from your blood by your kidneys) as well as other variables such as age, sex, and race. However, as CNN states, “When it comes to race, doctors have only two options: Black or ‘Other’.”

The problem stated by the article is that “Race isn’t a biological category. It’s a social one….Ancestry is biological. Where we come from — or more accurately, who we come from — impacts our DNA. But a patient’s skin color isn’t always an accurate reflection of their ancestry…A patient with a White mother and Black father could have a genetic mutation that typically presents in patients of European ancestry…but a doctor may not think to test for it if they only see Black skin.”

As a result, there is now a push to remove race as a variable in eGFR calculations, however that too is controversial. Via the CNN article:

“[Dr. Neil Powe, chief of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital,] worries simply eliminating race from these equations is a knee-jerk response — one that may exacerbate health disparities instead of solve them. For too long, Powe says, doctors had to fight for diversity in medical studies.

The most recent eGFR equation, known as the CKD-EPI equation, was developed using data pooled from 26 studies, which included almost 3,000 patients who self-identified as Black. Researchers found the equation they were developing was more accurate for Black patients when it was adjusted by a factor of about 1.2. They didn’t determine exactly what was causing the difference in Black patients, but their conclusion is supported by other research that links Black race and African ancestry with higher levels of creatinine…”

You might be saying, “This is interesting, but why is the Computing Community Consortium (CCC) writing about it? What does it have to do with computing research?” Well, in 2018 the CCC held a visioning workshop on Sociotechnical Interventions for Health Disparity Reduction that made similar arguments in the context of sociotechnical interventions. The workshop convened over sixty researchers and practitioners in computing, health informatics, and behavioral medicine to develop an integrative research agenda regarding sociotechnical interventions to reduce health disparities — the differences in health and health outcomes in one group when compared to the larger population.

As the workshop report states, “In Western countries, groups which experience disparities in health outcomes include:

As the workshop report states, “In Western countries, groups which experience disparities in health outcomes include:

- People of lower socio-economic status (SES) based on income, wealth, education, and occupation;

- Racial and ethnic minority groups including African Americans, Latinos, Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, and Indigenous peoples;

- Rural and urban residents;

- Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people;

- People with disabilities; and

- Men or women (varies by health issue).” (p. 2).

Sociotechnical interventions utilize technology to help people monitor their health status and/or modify their behaviors to improve their health outcomes. As an example, an application that helps people to manage their hypertension. But, the workshop report argues, such an application must be capable of being both targeted and tailored in order to be truly effective. “Targeting means that an intervention’s design would be created specifically for a group’s needs — for example, a hypertension management application for African American women. Tailoring means that the needs of one person are assessed and the system’s output personalized based on those needs [58] — for example, a hypertension management application for a specific African American woman.” (p. 13). Thus, simply categorizing someone as “Black” or “Other” is not satisfactory for some sociotechnical interventions, similarly to how such broad categorization may fail to produce a truly accurate eGFR.

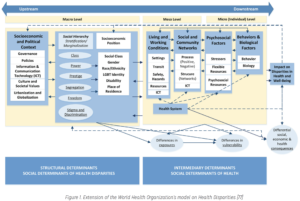

The workshop report encourages the use of upstream interventions over downstream interventions. Upstream interventions are those which affect a large group of people (e.g. public policy or economic regulations), whereas downstream interventions are those which apply only to a smaller group or an individual (e.g. an app on your phone that tells you to go for a walk). The report states,“A limitation with current sociotechnical interventions is their overwhelming focus on downstream interventions, with most interventions designed to help individuals adopt healthy behaviors or better manage illness. However, equity-focused systematic reviews have shown that downstream health behavior interventions tend to be less effective for marginalized populations than those that operate further upstream [19].”

From page 4 of the workshop report: Figure 1. Extension of the World Health Organization’s model on Health Disparities [77]

In both computing and medicine there is a need to more deeply understand the relationship between the technologies we use to monitor and improve people’s health and their actual, lived experiences.

If you want to hear more about the Health Disparity Reduction workshop, the two most recent episodes of the CCC’s official podcast Catalyzing Computing feature an interview with workshop co-organizer Katie Siek, who is also a CCC Council Member and the Chair of Informatics at Indiana University – Bloomington. In those episodes, Dr. Siek discusses the health disparities workshop as well as fitness trackers, data ownership, and aging in place. Listen to those episodes here and find the full Health Disparity Reduction report here.

[58] Schmid KL, Rivers SE, Latimer AE, Salovey P. Targeting or Tailoring? Maximizing Resources to Create Effective Health Communications. Mark Health Serv. NIH Public Access; 2008;28: 32.

[19] Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, Tugwell P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67: 190–193.

[77] Pain E. A New Funding Model for Scientists. Science. 14 Jan 2015. doi:10.1126/science.caredit.a1400012